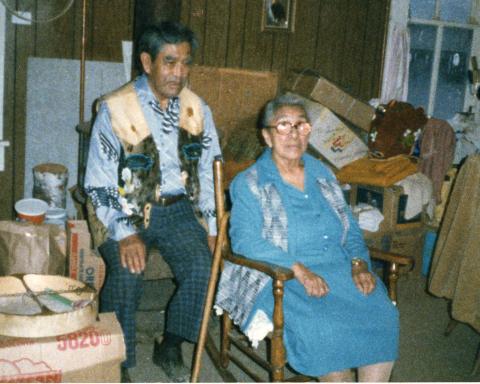

George Dalton, Sr. and Jesse Dalton

George Dalton, Sr. was born at his parents’ fish camp at the outlet from Dundas Lake in 1897. He was keeper of the Wolf house in Hoonah, Ak. He was Eagle moiety of the Kaagwaantaan clan, of the Kaagwagaani Hit (Burned Out House) and a child of the T'akdeintaan. He had several names; Stoowukaa, Kaadeik (one of these translates as Ocean Breaker) and as a peacemaker the title Tsalxaan Guwakaan (meaning Mt. Fairweather Peacemaker). He inherited the name Taulxan Gowukan from his brother, the late Jimmy Martin, the name meant "Fairweather Mountain Peace Dancer". (From Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian genealogy of Canada and Alaska, https://wc.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=klea&id=I22860)

He was noted as a tradition-bearer and peace maker for his clan. He could remember attending the big potlatch at Sitka in 1904; he and his family traveled part of the way by dugout canoe and part of the way by sailing schooner. He was one of the last people to know how to carve Spruce canoes; he helped his father and uncle make them in the early 1900's. He directed the carving of two sea otter hunting canoes in the late 1980's. One each was carved in Hoonah and in Glacier Bay. He worked at his father's fish camp on the Dundas River, which is now part of Glacier Bay National Park and maintained a cabin on Garforth Island on Muir Inlet inside the park.

He married to Jessie Starr in 1919. He and Jessie had fourteen children, seven of whom died young.

He was a commercial fisherman; he owned the F/V Washington; it was famous for its large seine catches. In 1945 he caught 45,000 salmon in one day. He was an excellent fisherman who for a number of years was Glacier Bay Lodge’s principal source of salmon. Commercial fisherman Floyd Peterson, also of Hoonah, recalled Dalton catching big king salmon in Glacier Bay in the middle of summer when there weren’t supposed to be any to be had (From Navigating Troubled Waters: Part 1: A History of Commercial Fishing in Glacier Bay, Alaska Part 2: Hoonah’s “Million Dollar Fleet”).

In the book George and Jessie Dalton are interviewed by Richard Newton in Hoonah, Alaska on June 21, 1979, George and Jessie speak a great deal about subsistence living in general, and, specifically smoking, preserving meat, hemlock sap-sux', rhizomes-k'wutl, tseit, three different kinds of caches, halibut skin bag at Lituya Bay found by Russians, seaweed, Tlingit houses with open smoke holes with use of slate edges for lumber, proper time to dig rhizomes and tseit, halibut fishing, use of whole fish, and conservation.

George Dalton, Sr. passed into the forest in February, 1991.

Jessie Dalton, Tlingit name Daax'wudaak & Naa tla'a, T’akdeintaan, Yéil Kúdi Hít (Raven, Kittywake’s Nest House).

"She was the eldest one of the tribe," Hilda See of Hoonah told the Juneau Empire. "She was called the mother of the tribe.... It's part of history going along (From the Sitka Sentinel).

Jessie Dalton’s “Speech for the Removal of Grief” in 1968 at the memorial potlatch for Nora Dauenhauer’s departed uncle Jim Marks is highly regarded in multiple literary, anthropology and historical circles as a beautiful and powerful traditional speaking and has been widely read, cited and studied.

“Jessie married George Dalton on May 18, 1919, an arranged marriage that took her out of Sheldon Jackson School and into adult life earlier than she would have liked. But she complied with her parents’ wishes, and she and George lived in Tenakee, near her parents, for the first years of their life together. The first five of her fourteen children were born there. And in Tenakee her father and her husband built the Tlingit, the Dalton couple’s first boat. The young couple moved to Hoonah, George’s home, in 1926 and have made that their home ever since.

Jessie’s life has been an active one, raising her children, taking care of her household, gathering foods in season and putting them up for winter, and earning a cash income from cannery work. The full schedule of Jessie’s life has left little time to follow personal pursuits, but she still managed to become a successful bead worker, selling moccasins and other beaded items for cash from time to time.

Jessie wanted to be educated in the Sheldon Jackson School and cajoled her indulgent father in letting her go. But even then, eager as she was to learn the new ways, she had the independence of judgement to realize that the prohibition against the speaking of Tlingit was a bad policy. And she rebelled against it, carefully, by deliberately speaking her language whenever she was out of earshot of the school authorities. She learned to read and write in English, but she maintained her fluency in

Tlingit, and cultivated her knowledge of Tlingit traditions. Her mastery is reflected in her public speaking. She is a primary spokesperson for her generation, and, as a member of the paternal grandparent clan of the deceased, was a major speaker at the memorial for Jim Marks.

Jessie has a flexibility rarely found, and always admired, that give her the conviction to hold on to the principles and values of her traditional culture while still embracing the conveniences and pleasures of the new. She has survived on her selectivity.” From Haa Tuwunaagu Yis, for Healing Our Spirit: Tlingit Oratory edited by by Nora and Richard Dauenhauer:

Jessie Dalton passed into the forest in 1997.